Written by Contributor

Winnie Nielsen

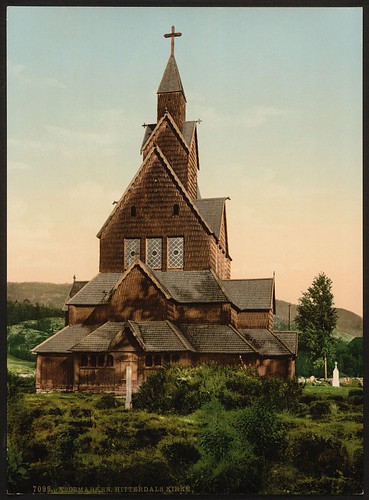

Christmas was primarily a religious celebration. It was comprised of a special meal on Christmas Eve with specific prayers, the reading of Bible verses, and singing of hymns. The meal was celebratory and followed by the opening of a few handmade gifts.

The celebration included many special foods spread on the table dressed in the best tablecloth available. It was the true smorgasbord which everyone looked forward too.The family gathered round together to hear the traditional readings and sing together while savoring the bounty of special dishes reserved for the occasion. Christmas Day was celebrated with a traditional early morning trip to church for a special service.

The Norwegians spent the late fall months, following the harvest, with preparing for the Christmas Eve celebration. Chores included the butchering of hogs( for the traditional roast pork dinner and special sausages), the making of plenty of candles from the tallow, the brewing of homemade beer, and right before Christmas, a thorough cleaning of the home from top to bottom. Right before Christmas Eve, special curtains or wall hangings were then placed, fresh straw was laid on the floor, a special tablecloth was laid on the table, and early in the day of December 24, everyone received a hot bath and was scrubbed from head to toe. Then, new fresh clothes were put on for the special Christmas Eve celebrations. Cleanliness was considered mandatory to prepare for the feast and most important celebration of the year. Early celebrations did not include a Christmas Tree.

The Norwegians spent the late fall months, following the harvest, with preparing for the Christmas Eve celebration. Chores included the butchering of hogs( for the traditional roast pork dinner and special sausages), the making of plenty of candles from the tallow, the brewing of homemade beer, and right before Christmas, a thorough cleaning of the home from top to bottom. Right before Christmas Eve, special curtains or wall hangings were then placed, fresh straw was laid on the floor, a special tablecloth was laid on the table, and early in the day of December 24, everyone received a hot bath and was scrubbed from head to toe. Then, new fresh clothes were put on for the special Christmas Eve celebrations. Cleanliness was considered mandatory to prepare for the feast and most important celebration of the year. Early celebrations did not include a Christmas Tree.

Christmas trees came to Norway and to the US from immigrants of German descent. Original celebrations were focused on the religions traditions, the special foods, a few homemade knitted gifts, or sometimes small children were given handcrafted toys made out of wood or a cloth doll for a girl.

Christmas Day, after church, was a time to visit with friends or receive friends at home. Sharing coffee and special cookies and other foods were important as a way to show appreciation and thanks to neighbors and friends.

Norwegians also had a custom called Julebukking, which reminded me of our Halloween traditions. The week after Christmas , people dressed up in scary costumes and went from door to door seeing if people could identify them. Those who played along invited the dressed friends inside for cookies and other treats. Sometimes the Julebukking ended up in mischief and Americans found the tradition distasteful. They pushed back on the immigrants with such disfavor that the tradition was dropped as fewer and fewer people participated or were unwelcomed in neighborhoods. What was interesting to me was how superstitious the Norwegians were about Christmas.

Like early Halloween and Samhain celebrations, people worried about evil spirits troubling them on Christmas Eve and special efforts were taken to appease spirits who might be about the home and farm. For Norwegians, Christmas Eve was the time when the veil between the living and the dead was the thinnest. Julebukking was the effort to make fun of and taunt others about lurking unwanted spirits at their doors! In addition to wandering sprits, appeasing the "Nisse" who lived on the farm, was also important. Nissen, the legendary elves, were thought to live among the farms and were responsible for ensuring that nothing bad happened to the animals or the farm. They did, however, expected a Christmas treat in return for their services, so a bowl of Christmas Porridge (flotegrot) was always promptly left out on Christmas Eve.

As the tradition of the Christmas Tree grew in favor with Americans, it became part of the celebrations at churches and schools. Norwegian children, who attended the public schools, were exposed to the growing favorite tradition. Since schools were so central to immigrant communities, the annual school Christmas pageant, became an important holiday tradition to the families. The pagent included a big Christmas tree and all the children received a little gift at the end of the school program. Lutheran churches also added a celebration at the home of the pastor around a big Christmas Tree as part of the festivities. By the time of World War I, Christmas trees were becoming important in the pageantry and the immigrants found that they were something worth adding to the traditions of the Old World. The children really pushed the idea of a tree at home as well.

The idea of Santa Claus entered the American scene in 1834 with the famous poem of The Night Before Christmas. Again, the idea of children getting gifts that had to be bought in stores was alien to Norwegian immigrant thinking. Norwegians held fast that the primary focus of Christmas should be the Old World traditions of the prayers, hymns, and foods of the Christmas Eve celebration. Slowly, however, as children were more exposed to American traditions in their schools and churches, and once married moved away from the farms to cities, the acceptance and embracing of store bought gifts and Santa Claus became woven into their own family celebrations.

World War II, brought a huge surge of patriotism in the US and immigrants joined in to embrace the efforts and wanted to be seen as patriotic in their new land. With that came even more acceptance of the American way of life and families were less inclined to stress speaking and acting in ways that separated them from other Americans.

And in Europe, with the Nazi 5 year occupation of Norway, German Christmas customs of Advent Calendars and Christmas trees saturated the cultural markets resulting in more Norwegians adding those traditions to the traditional ones.

It seems that as the immigrants melted into the melting pot of America, the Christmas traditions that were most preserved were those of serving special foods. In the early 1970s, young people wanted to know more about their roots and selected those traditions from the Old Country that seemed best for them. There was a resurrection of the popularity of Lutefisk, special breads and cookies, and the singing of old hymns again. Families added these elements back into their existing American Christmas traditions to teach their children about their Norwegian heritage. Today, immigrant communities share Lutefisk dinners, St. Lucia festivals, and bakeries full of long time favorite cookies like Pepperkakor, Sandbakkels, KrumKake, and Julebrot.

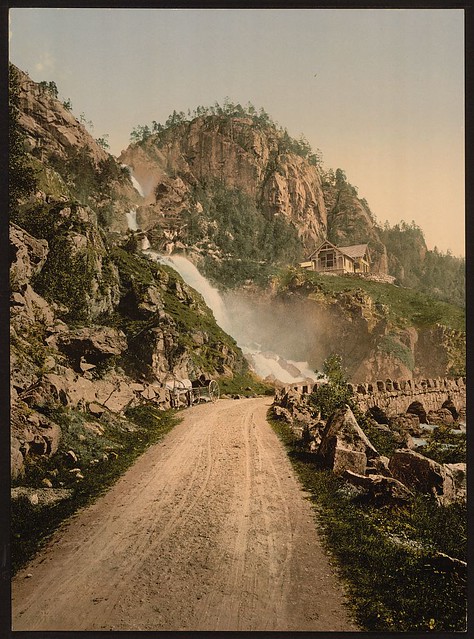

Keeping Christmas is a fascinating read about the immigrant experience of finding a new home in America while striving to maintain the pride of their Norwegian heritage. It was not an easy transition and many immigrants moved to the unsettled prairies of Kansas , Oklahoma, Nebraska and Iowa to homestead. They endured many hardships of getting established and growing sustainable communities. Christmas was the one celebration that brought everyone together in thanksgiving to celebrate their heritage. In enjoying the Old World traditions, a much needed winter respite occurred. The sharing of familiar foods and traditions renewed their ties to one another and lifted their spirits that coming to America was worth the hard work and leap of faith that was taken to leave their beloved Norway.

|

| Norwegian winter post card, SOURCE |

Christmas Day, after church, was a time to visit with friends or receive friends at home. Sharing coffee and special cookies and other foods were important as a way to show appreciation and thanks to neighbors and friends.

Norwegians also had a custom called Julebukking, which reminded me of our Halloween traditions. The week after Christmas , people dressed up in scary costumes and went from door to door seeing if people could identify them. Those who played along invited the dressed friends inside for cookies and other treats. Sometimes the Julebukking ended up in mischief and Americans found the tradition distasteful. They pushed back on the immigrants with such disfavor that the tradition was dropped as fewer and fewer people participated or were unwelcomed in neighborhoods. What was interesting to me was how superstitious the Norwegians were about Christmas.

Like early Halloween and Samhain celebrations, people worried about evil spirits troubling them on Christmas Eve and special efforts were taken to appease spirits who might be about the home and farm. For Norwegians, Christmas Eve was the time when the veil between the living and the dead was the thinnest. Julebukking was the effort to make fun of and taunt others about lurking unwanted spirits at their doors! In addition to wandering sprits, appeasing the "Nisse" who lived on the farm, was also important. Nissen, the legendary elves, were thought to live among the farms and were responsible for ensuring that nothing bad happened to the animals or the farm. They did, however, expected a Christmas treat in return for their services, so a bowl of Christmas Porridge (flotegrot) was always promptly left out on Christmas Eve.

As the tradition of the Christmas Tree grew in favor with Americans, it became part of the celebrations at churches and schools. Norwegian children, who attended the public schools, were exposed to the growing favorite tradition. Since schools were so central to immigrant communities, the annual school Christmas pageant, became an important holiday tradition to the families. The pagent included a big Christmas tree and all the children received a little gift at the end of the school program. Lutheran churches also added a celebration at the home of the pastor around a big Christmas Tree as part of the festivities. By the time of World War I, Christmas trees were becoming important in the pageantry and the immigrants found that they were something worth adding to the traditions of the Old World. The children really pushed the idea of a tree at home as well.

The idea of Santa Claus entered the American scene in 1834 with the famous poem of The Night Before Christmas. Again, the idea of children getting gifts that had to be bought in stores was alien to Norwegian immigrant thinking. Norwegians held fast that the primary focus of Christmas should be the Old World traditions of the prayers, hymns, and foods of the Christmas Eve celebration. Slowly, however, as children were more exposed to American traditions in their schools and churches, and once married moved away from the farms to cities, the acceptance and embracing of store bought gifts and Santa Claus became woven into their own family celebrations.

World War II, brought a huge surge of patriotism in the US and immigrants joined in to embrace the efforts and wanted to be seen as patriotic in their new land. With that came even more acceptance of the American way of life and families were less inclined to stress speaking and acting in ways that separated them from other Americans.

And in Europe, with the Nazi 5 year occupation of Norway, German Christmas customs of Advent Calendars and Christmas trees saturated the cultural markets resulting in more Norwegians adding those traditions to the traditional ones.

It seems that as the immigrants melted into the melting pot of America, the Christmas traditions that were most preserved were those of serving special foods. In the early 1970s, young people wanted to know more about their roots and selected those traditions from the Old Country that seemed best for them. There was a resurrection of the popularity of Lutefisk, special breads and cookies, and the singing of old hymns again. Families added these elements back into their existing American Christmas traditions to teach their children about their Norwegian heritage. Today, immigrant communities share Lutefisk dinners, St. Lucia festivals, and bakeries full of long time favorite cookies like Pepperkakor, Sandbakkels, KrumKake, and Julebrot.

Keeping Christmas is a fascinating read about the immigrant experience of finding a new home in America while striving to maintain the pride of their Norwegian heritage. It was not an easy transition and many immigrants moved to the unsettled prairies of Kansas , Oklahoma, Nebraska and Iowa to homestead. They endured many hardships of getting established and growing sustainable communities. Christmas was the one celebration that brought everyone together in thanksgiving to celebrate their heritage. In enjoying the Old World traditions, a much needed winter respite occurred. The sharing of familiar foods and traditions renewed their ties to one another and lifted their spirits that coming to America was worth the hard work and leap of faith that was taken to leave their beloved Norway.